Nearly one third of people killed by US police since 2015 were running away, driving off or attempting to flee when the officer fatally shot or used lethal force against them, data reveals.

In the past seven years, police in America have killed more than 2,500 people who were fleeing, and those numbers have slightly increased in recent years, amounting to an average of roughly one killing a day of someone running or trying to escape, according to Mapping Police Violence, a research group that tracks lethal force cases.

In many cases, the encounters started as traffic stops, or there were no allegations of violence or serious crimes prompting police contact. Some were shot in the back while running and others were passengers in fleeing cars.

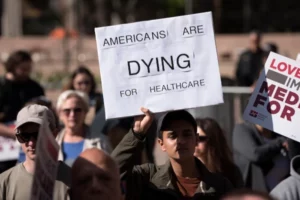

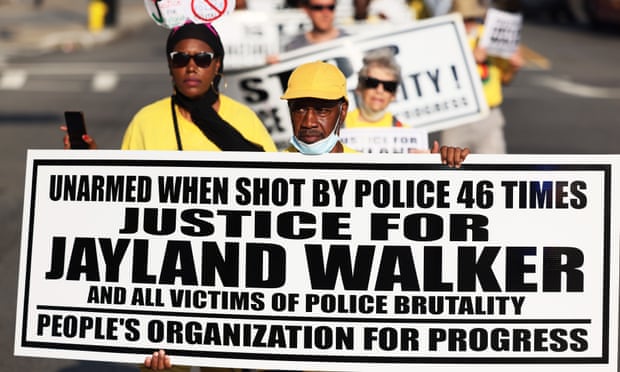

Two recent cases have sparked national outrage and protests. In Akron, Ohio, on 27 June, officers fired dozens of rounds at Jayland Walker, who was unarmed and running when he was killed. And last week, an officer in San Bernardino, California, exited an unmarked car and immediately fired at Robert Adams as he ran in the opposite direction.

Despite a decades-long push to hold officers accountable for killing civilians, prosecution remains exceedingly rare, the data shows. Of the 2,500 people killed while fleeing since 2015, only 50 or 2% have resulted in criminal charges. The majority of those charges were either dismissed or resulted in acquittals. Only nine officers were convicted, representing 0.35% of cases.

The data, advocates and experts say, highlights how the US legal system allows officers to kill with impunity and how reform efforts have not addressed fundamental flaws in police departments.

“In 2014 and 2015, at the beginning of this national conversation about racism in policing, the idea was, ‘There are bad apples in police departments, and if we just charged or fired those particularly bad officers, we could save lives and stop police violence,’” said Samuel Sinyangwe, data scientist and policy analyst who founded Mapping Police Violence, but “this data shows that this is much bigger than any individual officer.”

‘Hunted down’

US police kill more people in days than many countries do in years, with roughly 1,100 fatalities a year since 2013. The numbers haven’t changed since the start of the Black Lives Matter movement, and they haven’t budged since George Floyd’s murder inspired international protests in 2020.

The law has for years allowed police to kill civilians in a wide variety of circumstances. In 1985, the US supreme court ruled that officers can only use lethal force against a fleeing person if they reasonably believed that person was an imminent threat. But the court later said that an officer’s state of mind and fear in the moment was relevant to determining whether the shooting was warranted. That means a killing could be considered justified if the officer claimed he feared the person was armed or saw them gesturing toward their waistband – even if it turned out the victim was unarmed and the threat was nonexistent.

In 2022 through mid-July, officers have killed 633 people, including 202 who were fleeing. In 2021, 368 victims were fleeing (32% of all killings); in 2020, 380 were fleeing (33%); and in 2019, 325 were fleeing (30%), according to Mapping Police Violence. The data is based on media reports of people who were trying to escape when they were killed, and it is considered incomplete. In roughly 10% to 20% of all cases each year, the circumstances surrounding the shootings are unclear.

Black Americans are disproportionately affected, making up 32% of individuals killed by police while fleeing, but only accounting for 13% of the US population. Black victims were even more overrepresented in cases involving people fleeing on foot, making up 35% to 54% of those fatalities.

“If a person is running away, there is no reason to chase them, hunt them down like an animal and shoot and kill them,” said Paula McGowan, whose son, Ronell Foster, was killed while fleeing in Vallejo, California, in February 2018. The officer, Ryan McMahon, said he was trying to stop Foster, a 33-year-old father of two, because he was riding his bike without a light. Within roughly one minute of trying to stop him, the officer engaged in a struggle and shot Foster in the back of the head. Officials later claimed that the unarmed man had grabbed his flashlight and presented it “in a threatening manner”.

“These officers are too amped up and ready to shoot,” said McGowan, who for years advocated that the officer be fired and prosecuted. Instead, the officer went on to shoot another Black man, Willie McCoy, one year later; he was one of six officers who fatally shot the 20-year-old who had been sleeping in his car. The officer was terminated in 2020 – not for killing McCoy or Foster, but because the department said he put other officers in danger during the shooting of McCoy.

The city paid Foster’s family $5.7m in a civil settlement in 2020, but did not admit wrongdoing. A lawyer for McMahon previously said the officer was attempting to “simply talk to Mr Foster” when he fled, adding that McMahon “believed his actions were reasonable under the circumstances”. Vallejo police did not respond to a request for comment.

“Not only do these officers get away with it, they get to move on to bigger and better jobs while we’re left shattered and are still trying to pick up the pieces,” said Miguel Minjares, whose niece, 16-year-old Elena “Ebbie” Mondragon, was killed by Fremont, California, police.

“You shoot into a moving car, which you shouldn’t have done, and you weren’t even close to hitting the person you were trying to target. And now you’re a sniper?” said Minjares. “When I hear sniper, I think of precision. It boggles my mind. It shows the entitlement of officers and the police department, they just put people where they want them, it doesn’t matter what they did. It’s confusing and it’s heart wrenching.”

In June, five years after the killing, the family won $21m in a civil trial, but it’s unclear if Fremont has changed any of its policies or practices.

A Fremont spokesperson declined to comment on the Mondragon case and did not respond to questions about its policies.

The push to prevent the killings

In the rare cases when prosecutors do file criminal charges against police who killed fleeing people, the process often takes years and typically concludes with victory for the officer, either with judges or prosecutors themselves dismissing the charges or jury acquittals.

In one Florida case where an officer was investigating a shoplifting and fatally shot a man fleeing in a van, prosecutors filed charges and then dropped the case a week later, saying that after a review of evidence, it “became apparent it would be incredibly difficult to obtain a conviction”. In a Hawaii case where officers killed a 16-year-old in a car, a judge last year rejected all charges and prevented the case from going to trial.

With the criminal system deeming nearly all of these killings lawful, advocates have argued that cities should reduce the unnecessary police encounters that can turn deadly, such as ending traffic stops for minor violations and removing police from mental health calls. There’s also been a growing effort to ban officers from shooting at moving cars.

California passed a major law in 2019 meant to restrict use of deadly force to cases when it was “necessary” to defend human life, not just “reasonable”, and stating that an officer can only kill a fleeing person if they believe that person is going to imminently harm someone. The new law also dictated that prosecutors must consider the officer’s actions leading up to the killing, which police groups had argued were irrelevant under the previous standards.

But after its passage, police departments across the state refused to comply and update their policies, said Adrienna Wong, senior staff attorney at the ACLU of southern California, which backed the bill. That’s only now starting to change after years of legal disputes.

“I think we’re going to start to see prosecutors consider all the elements of the new law, but I’m frankly not holding my breath based on the track record of prosecutors in the state. We never thought this law was going to be a full solution.”

(published on July 28, 2022, in The Guardian by Sam Levin)