THE CIELO VISTA WALMART Supercenter in El Paso, Texas, is located east of downtown, near most of the city’s Mexican American neighborhoods and about six miles from the Bridge of the Americas, which connects the US community to its Mexican neighbor, Ciudad Juárez. The store keeps its doors open 17 hours a day, seven days a week, and it’s almost always busy. Like all big-box stores, the Walmart sits on the edge of a sprawling parking lot.

“Vanlife” devotees and people living out of their cars know the parking lot as a place to access restrooms and park overnight. Locals and middle-class cross-border shoppers from Mexico know the store for its low prices and aggressive marketing. For Josiah Heyman, a scholar at the University of Texas at El Paso who for years has studied the borderlands and immigration through the lens of cultural anthropology, the big asphalted parcel can also be seen as a symbol of a worldview. “The view across the Walmart parking lot is the impression that there are these hordes of immigrants who are poor,” he said, offering an all-too-common perception (which he does not share) of Latinos and Latin American immigrants. “And they’re men, because there’s this gendered fear of darker-skinned men hanging around.”

LIKE EVERYONE IN THIS border city of a quarter million people, Heyman, a curly-haired, spectacled man originally from Oklahoma, has been trying to make sense of what took place at the Cielo Vista Walmart three years ago. Late on an August morning in 2019, a 21-year-old white man from an upper-middle-class suburb of Dallas pulled into the parking lot when approximately 3,000 people were in and around the store. Dressed in a black shirt and cargo pants and carrying an AK-47, the man opened fire on whoever crossed his path, targeting shoppers in the parking lot and throughout the store’s aisles. The shooter killed 23 people and wounded another 26. Today, a memorial to the victims stands at the edge of the parking lot. It’s been dubbed the “Grand Candela”—a collection of 30-foot-tall aluminum columns in remembrance of the people who were murdered.

Before his killing rampage, the shooter published a white supremacist text online that seemed galvanized by the view of the Walmart parking lot. The El Paso killer expressed support for a self-described “eco-fascist” in Christchurch, New Zealand, who, just four months earlier, had murdered 51 people in a terrorist act targeting immigrants. The Walmart shooter wrote, “I am simply defending my country from cultural and ethnic replacement brought on by an invasion.”

Contemporary eco-fascist rhetoric cannot show a connection between environmental destruction and immigration for a simple reason: There isn’t one.

The killer went on to lay out a plan to separate the United States into different territories according to race and cited the “great replacement theory”—a conspiracy theory claiming that whites are being demographically and culturally replaced by nonwhites. He blamed Latinos for taking away native-born Americans’ jobs and for destroying the environment. The shooter advocated for “decreasing” their numbers. “If we can get rid of enough people, then our way of life can be more sustainable,” he wrote. According to federal prosecutors, the attack was meant to scare Latinos into leaving the United States.

In 1998, Heyman published a monograph, Finding a Moral Heart for US Immigration Policy, which was intended as a response to border vigilantism and anti-immigrant policies—a fever of xenophobia that has only grown more inhumane since then. “I wrote that book not to be optimistic,” he told me, “but to think about a vision of what could be done. I wasn’t really happy with tearing everything down without offering something else in its place.” How about seeing immigrants with compassion? Heyman asked. What if we drafted policies that recognized the drivers of migration?

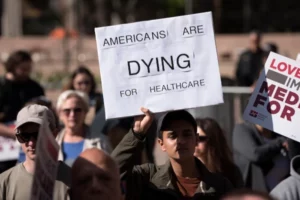

More than two decades after Heyman called for “finding a moral heart,” immigration policy in the United States is more polarized than ever, with a growing number of US citizens expressing opposition to immigration. The Cielo Vista Walmart terrorist attack was horrific evidence of the violence lurking just below the surface of white nationalism.

The Walmart massacre also represented the first lethal outburst of American eco-fascism—that is, violence in the name of environmental conservation. The El Paso terrorist attack catapulted into public awareness the “greening of hate” that has long haunted the American environmental movement. In the 1990s, Betsy Hartmann, professor emerita of development studies at Hampshire College, coined the term greening of hate as a way to describe how scapegoating immigrants for environmental degradation is a way to lure environmentalists into the folds of the nativist movement.

HARTMANN HAD BEEN INVITED to debate Virginia Abernethy of the nonprofit Carrying Capacity Network at an environmental law conference in Oregon in 1994. “I quickly realized I wasn’t debating a fellow environmentalist or family-planning advocate,” Hartmann later wrote, “but rather an anti-immigrant activist for whom population and carrying capacity were euphemisms for circling our wagons and closing our borders.” She has been tracking such discourse ever since, warning how it “too easily plays into the hands of apocalyptic white nationalism.”

The exact contours of eco-fascist ideology can be hard to pin down, given that it’s such a mash of conspiratorial white supremacy. But in its broadest definition, eco-fascism sees itself as a kind of environmentalism that advocates violence or the exclusion of some groups of people due to their race or class—or both. Since the 2019 terrorist attack in El Paso, eco-fascism has continued to be a touchstone for some members of the violent right wing. The shooter who killed 10 Black people at a Buffalo, New York, grocery store last May described himself as an “ethno-nationalist eco-fascist.”

“Eco-fascism has become kind of a popular buzzword for talking about these terrorist attacks that have happened in the last few years,” Aaron Flanagan, a research analyst with the Southern Poverty Law Center who studies white-power movements across several ideologies, told me. “But largely, I encourage people to look at the historical legacy of white supremacy.” The term eco-fascism is confusing, Flanagan said, as it doesn’t encapsulate the insidious ways that white dominance and exclusion have been foundational to American conservation.

It’s true that strands of white supremacist thinking run deep in the history of American environmentalism. It’s also true that contemporary eco-fascist rhetoric cannot show a connection between environmental destruction and immigration for a simple reason: There isn’t one. Blaming immigrants for widespread environmental challenges is bogus. Immigration to the US is not considered a major source of population growth, as immigrants make up about 14 percent of the population, the same as in 1870. And, in any case, all the available evidence suggests that it’s not working-class immigrants but large-scale industry and affluent, US-born Americans that are driving consumerism, climate change, and the loss of wildlife habitat.

Yet within some right-wing circles, the paranoia persists that immigration is, somehow, a cause of environmental destruction. So then, what do we call a 21-year-old who holds such hate for brown people in a brown city? What does it mean when seven out of 10 Republicans believe in the great replacement theory, according to a recent poll by the Southern Poverty Law Center? It might be tempting to dismiss such fear as mere delusions, but it would be dangerous to do so. The hate-filled view of the El Paso Walmart parking lot does not reflect reality, yet it’s one that keeps spreading online, shaping perceptions and opinions that have proved challenging to explain, difficult to extricate, and deadly.

ON JULY 19, FOX NEWS host Tucker Carlson went off on one of his trademark monologues that blend together fact and fiction to promote the idea that the United States is—or should be—a white nation. “Sometime around 1965,” he told the camera, “our leaders stopped trying to make the United States a hospitable place for American citizens, their constituents, to have their own families. That used to be considered the central task of leadership, perpetuating the population. If people are happy and confident, they’ll have kids. They’re vested in the society. And if they’re not, they won’t.”

The mention of 1965 was a racist dog whistle. That year, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the landmark Immigration and Nationality Act. The law did away with national-origin quotas that favored immigration from northern and western Europe, and it led to a shift that we still see today in which a growing number of immigrants to the United States are coming from the Global South and a majority are arriving from Mexico (around 25 percent, according to the most recent numbers available). In the view of its proponents, the 1965 law created a more welcoming immigration system. “The bill . . . will not upset the ethnic mix of our society,” Senator Ted Kennedy told the Senate at the time. “It will not cause American workers to lose their jobs.”

Carlson and his audience see things differently. Carlson has become infamous (or famous, depending on one’s politics) for giving a sheen of respectability to white nationalist ideas. Among Fox News hosts and Republican elected officials, this is not unusual. During an interview with the network in 2021, Texas lieutenant governor Dan Patrick said that the immigrants entering the United States are “trying to take over our country without firing a shot.”

What makes Carlson’s white nationalism noteworthy is how explicitly he ties anti-immigration views to conservation ideals. Take his November 20, 2019, broadcast: “One of the greatest blessings we have as Americans is the amazing pristine beauty of our country,” he declared. “Even with 320 million people living here, this country still is not particularly crowded. . . . The old environmental movement understood that, and was why they campaigned for lower immigration levels—because crowded countries are never beautiful countries.” Carlson may not be an eco-fascist (he is careful, always, to say he doesn’t believe in white supremacy). Yet his statements represent a way of laundering some eco-fascist rhetoric.

As an ideology, eco-fascism has had a complex history. In their book, The Rise of Ecofascism: Climate Change and the Far Right, Sam Moore and Alex Roberts make a case for keeping the definition simple: “Perhaps the main purpose of [this] book as a whole is to convert popular worry about ‘ecofascism’ into more clear-eyed opposition to the forms of racialized power that are wielded over and through the environment, be they ‘fascist’ or not.” In other words, white dominance, exclusion, and hate have been foundational to the history of this country—and the American environmental movement, past and present, is not immune to these pathologies.

The dark web and social media have mutated and further radicalized understandings of US history. The authors of The Rise of Ecofascism argue that one thing that defines eco-fascism online is its absurdity—but that even its inherent confusions may not be enough to diminish its attractiveness to some people. “It is not the radicalism of these arguments that should give us pause so much as their strangely incoherent juxtapositions of disparate parts,” they write. “The nature politics that emerges from this wing of the Far Right . . . is both repugnant and trivial, although its danger is that neither will limit its spread.”

Today’s eco-fascist rhetoric is at once unprecedented and a long time coming. It represents one of multiple desperate attempts by the Right to scapegoat immigrants, despite the fact that the immigrant population is plateauing and despite the data that points to how prosperous Americans tend to drive much more consumption than working-class immigrants do.

In this era of conspiracy theories, however, facts and data can do only so much to advance the truth. Especially if, as in this case, the truth points to a long, troubling history of how one strain of US environmentalism has sought to make a link in the American mind between immigration and environmental destruction.

SPEAKING TO ME VIA a video call from a wood cabin in Oregon last summer, Hop Hopkins, the Sierra Club’s director of organizational transformation, wore his trademark felt cowboy hat and plaid shirt. “I don’t think most people are clear about eco-fascism and white nationalism,” he told me. “They think they are two different forests, but they actually come from the same seed.” Starting from this country’s foundation on the enslavement of Africans and the attempted annihilation of Indigenous peoples, racism permeates every aspect of US culture. As a product of this history, eco-fascism is not new, Hopkins argues. We just “haven’t been able to scale our awareness and knowledge of these pernicious movements as they’ve gained more traction and steam.” And this is very dangerous: As ecological breakdown becomes more acute, people of color and immigrants around the world will bear the brunt of its impacts. If eco-fascists have their way, people of color and immigrants will face an additional burden—more of them will be blamed for anthropogenic climate change.

When he joined the Sierra Club eight years ago, Hopkins admitted, neither the organization nor the larger environmental movement was ready to receive this complicated history. Today, there is growing consensus about just how entwined the roots of eco-fascism and the roots of American environmentalism really are.

In August 1901, one month before becoming the youngest president in US history, 42-year-old Theodore Roosevelt visited Colorado Springs and delivered a speech titled “Manhood and Statehood,” praising westward expansion. “It is a record of men who greatly dared and greatly did; a record of wanderings wider and more dangerous than those of the Vikings; a record of endless feats of arms, of victory after victory in the ceaseless strife waged against wild man and wild nature,” he declared. “The winning of the West was the great epic feat in the history of our race.”

Everyone in the audience would have understood that “our race” meant the white descendants of European colonists. As Indigenous peoples continued to face massacres and removals from their ancestral territories, Roosevelt would be lauded for establishing five national parks and four national monuments made up of Native territories. Meanwhile, his friend and fellow conservationist Madison Grant turned to racist pseudoscience to make a case for preserving the supposedly superior traits of America’s “Nordic” peoples. His book, The Passing of the Great Race, hugely influenced America’s first restrictionist immigration policies targeting non-Europeans as well as the articulation of the white supremacist ideology. Roosevelt praised the book. So did Adolf Hitler, who, in a letter to Grant, described it as his “bible.”

In the same year that Roosevelt delivered his “Manhood and Statehood” address, John Muir published Our National Parks, which would catapult him into national fame and make him among the country’s most prominent conservationists. Muir’s views about the “cleanliness” of nature were steeped in a white-centric worldview that was widespread among European Americans of that time. Other Sierra Club founders took such a worldview into more dangerous territory. Mountaineer and scientist Joseph LeConte was a Confederate sympathizer, and David Starr Jordan, the founding president of Stanford University, was a prominent eugenicist who pushed for the forced sterilization of Black and Indigenous people.

In the mid-20th century, the false idea that people of color had an outsize environmental impact continued to burble within the US environmental movement—even as the civil rights movement was beginning to overturn a white-centric worldview. In 1968, the Sierra Club published Paul and Anne Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb, which blamed poor nonwhites for ecological disaster. “Some of the most depressing situations are found in Latin America,” the Ehrlichs wrote. “There, politicians have generally been far behind those of Asia in recognizing overpopulation as a major source of their problems.”

The book singled out population growth in poorer nations—rather than total global resource consumption, mostly driven by wealthy nations—in predicting that hundreds of millions of people would starve to death in the following two decades. Those predictions proved untrue. But the book provided fuel to individuals and groups opposed to US immigration, voices that grew louder in subsequent years as they preached the myth that immigrants were a danger to the American environment.

Few people did more to advance that myth than a man considered to be the architect of today’s anti-immigration movement: John Tanton. Starting in the 1960s, he joined scores of environmental organizations and founded three—the Federation for American Immigration Reform, the Center for Immigration Studies, and NumbersUSA—that advocated for population control, nativism, and eugenics through environmentalist arguments. “North America cannot accommodate huge additional numbers—it is now quite fully occupied, with scarcely any virgin land or untapped resources awaiting settlers,” he wrote, absent supporting evidence, in 1994.

As part of his larger effort to bring such views into the mainstream, Tanton tried to make anti-immigration policy a centerpiece of the Sierra Club. On two separate occasions, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Tanton and his followers attempted to take over the Sierra Club’s board of directors to adopt an anti-immigration policy as part of the organization’s priorities. To the credit of the Sierra Club membership, both attempts failed. But they revealed the extent to which some environmentalists imagined a link between immigration and environmental problems. (Tanton died in 2019, two weeks before a terrorist opened fire on the Cielo Vista Walmart in El Paso.)

The efforts to weaponize environmental concerns in order to advance an anti-immigrant agenda continue. In 2021, Arizona’s attorney general, Mark Brnovich, sued the Biden administration on the grounds that it had failed to do an environmental impact study of its immigration policies. In his suit, Brnovich argued, “Migrants . . . directly result in the release of pollutants, carbon dioxide, and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, which directly affects air quality.”

IF EL PASO HAS the awful distinction of being the first place in the United States where eco-fascist ideas erupted in violence, it is also representative of something else: a place that is almost a reverse image of the white supremacist ideology fueling the great replacement theory. El Paso is a binational border city that’s home to Mexicans and Mexican Americans who work, study, shop, dream, live, and die like everyone else. This city with a roughly 80 percent Latino population is also steadily growing and thriving. The border community is a living challenge to the premise of eco-fascism: It shows us how immigrants and their descendants aren’t, in fact, responsible for environmental degradation. On the contrary, their inclusion in US society will be key for sustainable growth, environmental justice, and public land conservation. El Paso, and its firebrand Latino-led environmentalism, is a lab for America’s future.

I met Cemelli de Aztlan in El Paso on a 100°F spring day. We drove in her car with the air conditioning on, but it barely kicked in, so she kept the windows open as she took me on a “toxic tour” of El Barrio Chamizal. The neighborhood, meaning “thicket” in Spanish, is a hub of industrial activity in one of the oldest and poorest residential areas in south-central El Paso. De Aztlan is a community organizer with La Mujer Obrera, a Chicano, women-led organization that was founded in 1981 to take on local environmental fights along with labor, housing, and women’s rights campaigns in El Paso. As an organizer, she’s focused on getting this community of 8,000 people—especially its mothers and grandmothers—engaged in environmental and social justice issues.

In the mid-20th century, El Chamizal made sense for the folks who called it home: It was an affordable neighborhood where garment workers could be close to the factories where they toiled. Now the garment industry is gone, and heavily polluting recycling facilities have been grandfathered into the neighborhood. Local residents have had little choice but to live next to them.

De Aztlan drove by a small adobe home where her grandmother, a Mexican garment worker, used to live. She made another turn, and we crossed back into the industrial zone where her daughter’s school sits. Frederick Douglass Elementary used to be a school for Black children, and it remained segregated until 1956. Today, nearly all Douglass Elementary students are Latino and from low-income families.

Behind the school, she pointed out a mountain of metal: W. Silver, a recycling facility that extends across seven city blocks and takes in metals, electronics, and batteries. The facility generates a fine dust that blows into Douglass Elementary. “We’ve been able to pressure [the company] to get some of it moved, but the soil they left behind is still in need of a cleanup,” De Aztlan said. The company has reduced the amount of waste it dumps in El Chamizal and now ships some of it to Santa Teresa, New Mexico, a community a half-hour drive north of El Paso that’s 80 percent Latino.

De Aztlan took me by Interstate 10 to show me where 18-wheelers line up during rush hour, and by the bus depot, another major source of dangerous particulate matter that drifts into the Douglass Elementary playground. The American Lung Association ranks El Paso as the 12th-worst US city for ozone pollution, beating Chicago, with a population four times bigger. And El Chamizal is largely at the center of this pollution, with its truck emissions and high concentration of power plants and industrial boilers. Add to the mix steadily rising temperatures caused by climate change and you can begin to imagine how smog pollution in El Paso will likely become worse in coming years, and how it’ll affect some families more than others.

The story of El Chamizal—a working-class Latino community that’s facing the brunt of industrial encroachment and pollution and the impacts of climate change—is hardly unique. For years, researchers have found that on average, Black, Latino, and Asian people are exposed to higher than average levels of fine particle pollution. People of color, the EPA says, also face disproportionate negative impacts from climate change, including air pollution, flooding, and excessive heat.

At the same time, communities of color are more likely to be in favor of stronger environmental protections—very likely because they tend to be disproportionately affected by environmental abuses. According to a 2019 poll by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, Latinos and Blacks are more concerned than whites about climate change. This attitude extends to greater support for conserving water, reducing air pollution, and protecting wildlife. An estimated 69 percent of registered Latino voters polled said they were alarmed or concerned about global warming—compared with 49 percent of white respondents.

Calling themselves Familias Unidas del Chamizal, De Aztlan and other neighborhood women got together in 2017 to pressure local and state officials to regulate industry emissions. Within a year, they joined a coalition of environmental and community groups, including the Sierra Club, to sue the EPA. Their lawsuit claimed that for years the EPA ignored El Paso’s unsafe smog levels and failed to enforce the Clean Air Act.

In 2020, a court sided with Familias Unidas, and the EPA demanded the regulation of all new sources of pollution in the area. But the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality has appealed the decision, claiming the ozone pollution is coming from south of the border. Yet just 3.5 miles from El Chamizal (and north of the US-Mexico border), a Marathon Petroleum refinery remains one of the city’s largest industrial sources of dangerous pollutants, including PM2.5, PM10, volatile organic compounds, and nitrogen oxides. Familias Unidas del Chamizal is among many El Paso activist groups demanding that Marathon Petroleum be shut down. (The company is currently trying to renew its air permit for carbon monoxide and other pollutants.)

Joshua Blaine Simmons grew up three blocks from the Marathon Petroleum site. “My grandma would tell me, ‘Oh, look at the refinery!'” he told me, describing how the labyrinth of shiny metal stacks and pipes with flares and little blinking lights looked like a city from another planet. “‘It’s magical, like The Wizard of Oz.'” His grandma lived in that house for almost 50 years, and she died there at 64 with a long list of ailments. “As I learned the facts, I found out it wasn’t steam coming out of those smokestacks.”

A graduate in electrical engineering from the University of Texas at El Paso, Blaine Simmons had a steady job he didn’t love as an engineer when Donald Trump was elected president. He remembered feeling shaken by the news and by Trump’s nativist rhetoric and what it meant for people like him who cared for the environment. “So in 2018, I decided that I had enough of my job. I knew that solar was going to become a big thing for Sun City,” he said, using El Paso’s nickname.

Like other cities in the Southwest, El Paso is deep in a megadrought and experiencing temperatures that are, on average, 0.6°F to 1.2°F warmer than they were a decade ago. Rooftop solar makes a lot of sense for this region, with its 300 days of sun a year. Yet the city lags behind Austin and San Antonio for solar capacity per person. Blaine Simmons has made solar power adoption in his native El Paso his passion: He’s a board member of the local nonprofit Eco El Paso and a vice chair for the City of El Paso’s Regional Renewable Energy Advisory Council. He’s also on Democratic representative Veronica Escobar’s Climate Crisis Advisory Committee and a leading organizer with the El Paso chapter of the Sunrise Movement. At 35 years old, Blaine Simmons is considered “the boomer of the group.”

“We’re the ones that show up, and we annoy Marathon. We annoy city council,” he said with a smirk. One of Sunrise’s biggest goals is to get El Paso voters to approve a climate charter, inspired by the ideas behind the Green New Deal, which would be the first of its kind in Texas. If approved, the charter would help better prepare the city for climate disasters, invest in renewables, and advance climate justice. The group has gathered almost 40,000 signatures to get the amendment on the May 2023 ballot.

“I think we have the potential for everyone in El Paso to be a climate activist,” Ana Fuentes, a 25-year-old Sunrise organizer, told me. Going from neighborhood to neighborhood alongside Luis Enrique Miranda, 26, Fuentes connected with hundreds of El Pasoans and found that most of them were very receptive to the climate charter. What she and Miranda kept hearing, over and over, was how much rising temperatures and drier seasons were on locals’ minds, Fuentes said.

Seeing this Latino-led environmental activism at play in the same city that saw the deadliest attack on Latinos in modern US history, I wanted to know whether the rise of eco-fascism in general, or the 2019 terrorist attack in particular, had influenced these activists. “Yes,” Miranda told me, nodding gently. “We’re providing a vision where death isn’t involved. I think that’s one of the things we’re definitely trying to achieve with the climate charter—a counternarrative that is imagining a future where we fix things.”

One afternoon, as the temperature started to dip, I headed through rush-hour traffic toward downtown El Paso. Stuck behind the seemingly endless lines of 18-wheelers and giant pickup trucks, I rolled past El Paso’s natural and human-built landmarks. To my right was Biggs Army Airfield’s 4,000 acres and the Franklin Mountains behind it. Until 1965, the US military used the mountains as a shooting range. For decades, the local nonprofit Frontera Land Alliance has been trying to protect the range from future development so it can be used for outdoor recreation. Today, the 7,081-acre Castner Range is undergoing a munitions cleanup, and the land alliance is advocating for it to be declared a national monument.

I kept heading west on the interstate and eventually passed the Cielo Vista Walmart, where I glimpsed the memorial sculpture, which looks like a giant candle. To my left, the Marathon Petroleum refinery stood out with its blinking lights. Just past the refinery, I could spot the rust-color border wall and the hilly neighborhoods of Ciudad Juárez, mirror images of the barrios on the El Paso side of the international boundary. Less than two centuries ago, this region was one and the same Chihuahuan Desert. It still is. The two cities share air and an aquifer.

During our tour, De Aztlan had pointed to La Mujer Obrera’s community farm, Tierra Es Vida (Land Is Life), a pocket of bright green amid all the gray of heavy industry. “It’s always a balance between defending and creating,” she had told me as we drove around in the heat, focusing on everything that was damaged in the neighborhood. The community garden, she explained, “sustains not only the movement building but our sanity, our health.”

Back in El Chamizal by myself, I spotted a flyer by the garden entrance calling on local families to volunteer for community work. I peeked through the chain-link fence, and I could make out what the abuelas, the grandmothers, were growing in their small plots: chilies and tomatoes and corn and nopal cacti and herbs. The flyer read, “All are welcome.”

(from Sierra Magazine, Dec. 27, 2022, by Ruxandra Guidi)